- Convey the problem.

- Perform a silent demonstration of the solution/technique.

- Shade the essential steps.

- Practice.

- Provide feedback.

Part 3 explained the science behind selecting the optimal number of practice repetitions needed to learn a motor skill, the students' mindset during practice, and an observable means to measure learning. While task repetition is a valuable tool, practice is further enhanced by using skill transfer, varying environments, randomization, interleaved skills, deliberate rest, and being mindful of the length of practice sessions.

Motor learning is optimized when repetitions are done in a variable environment. In jiu-jitsu, instructors should actively encourage practicing with different partners during repetitive drilling so students can practice the technique on students with different body mass, body dimensions, strength, energy, levels of resistance, agility, and athleticism (Harvard University, 2011; Schmidt & Lee, 2019). Instructors should rotate partners during instruction to vary the students’ environments.

Randomization

Task repetition training can be optimized if instructors are mindful of the relationship between techniques. Techniques can be taught in “blocks,” like a bunch of techniques from one position, or “randomly,” wherein there is no apparent connection between the techniques whatsoever. In jiu-jitsu, blocked practice is the repetitive drilling of one technique, whereas random practice might involve students practicing multiple techniques from multiple positions.

Both types of practice have merits. In many students, blocked practice results in faster skill acquisition but decreased retention, inhibiting a student’s ability to apply the technique days after practice, whereas random practice results in better retention and application, but the skill takes longer to learn (Gill et al., 2018; Schmidt & Lee, 2019). Instructors should utilize both types of practice by varying the lesson format. Teach an assortment of techniques one day, then another day, teach techniques from only one position.

Skill Transfer

As mentioned in Part 3, synergy training applies essential elements of one skill to a new skill being taught to enhance learning. Studies suggest that students learn more information in less time and retain knowledge better than with simple task repetition training; therefore, instructors should teach techniques with similar mechanics (Patel et al., 2017). Part 3 used the Kimura shoulder lock, taught from the guard and half guard positions, as the techniques share many of the same principles.

Interleaving Practice

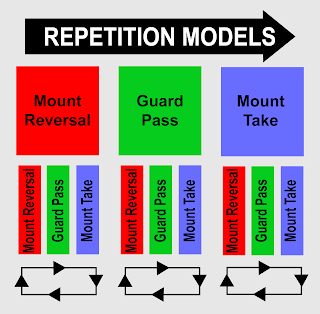

Task repetition training can be optimized even further by adding other techniques to the drill. Instead of repeating a new technique over and over, mix the new technique with other skills (Kim, 2021; Vleugels et al., 2020). For example, an instructor teaches the upa technique to reverse the mount into their opponent’s guard. After students practice the technique, the instructor teaches a guard pass to side control. Students continue to drill the upa technique but pass their training partner's guard after they reverse the mount. The instructor then teaches a knee cut from side control to establish the mount position. Students will continue to drill the mount reversal and guard pass techniques but finish the drill with the knee cut to mount. The students have effectively reversed roles during the drill and can alternate practice repetitions seamlessly. This multi-positional drill reinforces the first technique taught with each repetition while maximizing class time.

Rest

Providing short breaks during practice is helpful for students because learning is optimized if instructors provide additional demonstrations and feedback during short rest periods (Schmidt & Lee, 2019). As previously noted, the optimal number of repetitions to observe before providing group feedback is five, so after five repetitions, instructors could regroup the students to offer feedback, demonstrate the technique again, and address any issues observed. During the short rest period, instructors could vary the students’ environment by switching their partners, as noted above, before performing additional practice repetitions.

Length of Practice Sessions

Learning motor skills is affected by the length of practice, and for almost a century, researchers have attempted to determine the optimal amount. There is no benefit from any practice session lasting over four hours and the benefits of practice begin to deteriorate after only one hour (Ericsson et al., 1993). Other studies suggest that practicing a motor skill for two hours in one session is inefficient and that one hour is optimal because researchers found that shorter practices, despite resulting in less total practice over several weeks, still resulted in higher retention rates (Baddeley & Longman, 1978). Instructors should consider limiting practice sessions to less than two hours, and ideally only one hour. Instructors should understand that practice time does not include live sparring and “rolling,” as that is considered a performance, not practice. Since studies suggest poor retention after four hours of instruction, limiting seminars to only four hours would be optimal.

Application

- Teach techniques with similar mechanics.

- Change partners during drilling.

- Vary the format of the lesson. One day, teach techniques from an assortment of positions, and another day, teach techniques from only one position.

- Supplement instruction by teaching a sequence of techniques.

- After approximately five repetitions, provide a rest break to offer feedback, demonstrate the technique again, and address any issues observed.

- During breaks, instruct students to work with a different partner.

- Consider limiting practice sessions to less than two hours before doing live sparring and “rolling.”

- Limit seminars to four hours.

Summary

Task repetition training is useful; however, instructors can enhance learning by using skill transfer, varying environments, randomization, interleaved skills, and deliberate rest. Unfortunately, learning is only effective if the skills are retained in memory. Strategies to maximize memory retention and minimize decay are described in The Science of Teaching Jiu-Jitsu, Part 5: Retention.

About the Author

Professor Brian Bowers is a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt under Professor Chris Popdan with a decade and a half of grappling experience. He is the professor of The Hangout Jiu-Jitsu Club in Indianapolis, Indiana, and a coach at the Franklin, Indiana, Jiu-Jitsu Club. In 2024, Brian completed his professorship course under the Oswaldo Fadda lineage.

Brian is a federal law enforcement officer and a physical tactics and firearms instructor for his agency. He was also a firearm, physical tactics, and search and seizure instructor at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, where he continues to serve as an adjunct instructor. In 2024, Brian's role as a law enforcement officer and instructor, as well as being a jiu-jitsu black belt, earned him verification as an Invictus Law Enforcement Jiu-Jitsu Black Belt while The Hangout Jiu-Jitsu Club became an Invictus-affiliated club.

Having personally relied on jiu-jitsu techniques to protect his life, Brian advocates jiu-jitsu as essential knowledge for all law enforcement personnel. His dedication to this cause is evident in his involvement with the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association 111 Project, a non-profit organization dedicated to the safety of law enforcement personnel through support, education, training, and information sharing.

Brian's commitment to his students goes beyond the mat. With a Master of Science in Business Management, he leverages his formal education to cultivate deep, meaningful relationships with his students. His selfless dedication to serving their needs is evident in his use of research from psychology and neuroscience to optimize learning in any discipline he teaches. Brian uses science-based principles to educate jiu-jitsu practitioners, law enforcement students, law enforcement instructors, and jiu-jitsu instructors through The Hangout Journal.

References

Baddeley, A. D., & Longman, D. J. A. (1978). The influence of length and frequency of training session on the rate of learning to type. Ergonomics, 21.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100.

Gill, S. V., Pu, X., Woo, N., & Kim, D. (2018). The effects of practice schedules on the process of motor adaptation. Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions, 18.

Harvard University. (2011). How the body learns to make accurate movements: In motor learning, it’s actions not intentions that count. ScienceDaily.

Kim, T. (2021, November 3). New method to learn motor skills. Springer Nature.

Patel, V., Craig, J., Schumacher, M., Burns, M. K., Florescu, I., & Vinjamuri, R. (2017). Synergy repetition training versus task repetition training in acquiring new skill. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 5.

Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D. (2019). Motor learning and performance: From principles to application. Human Kinetics.

Vleugels, L. W. E., Swinnen, S. P., & Hardwick, R. M. (2020). Skill acquisition is enhanced by reducing trial-to-trial repetition. Journal of Neurophysiology, 123.